Fiji is an archipelago of over 330 islands—about a third of them inhabited—scattered across the South Pacific.

Although its total land area is relatively small, its maritime territory spans more than 1.2 million square kilometers, making Fiji a significant player in Pacific marine conservation and ocean governance.

The two largest islands—Viti Levu and Vanua Levu—are home to most of the population and infrastructure, while the outer islands range from densely forested volcanic peaks to flat, sandy atolls.

But, Fiji isn’t just beaches and hibiscus trees. It’s a network of islands, each with its own rhythm, shaped by migration, colonization, volcanic eruptions, and rituals.

After spending almost a full month at sea, we were craving some land adventures. And Fiji—with its towns, villages, coastlines, coral gardens, and ceremonies—was the perfect place to end our Pacific tour. So we rented a car and drove around most of Viti Levu, the main island.

(A note: We rented a sedan, having read that the roads were generally good—which they were. However, we couldn’t reach some mountain villages, which are accessible only by 4x4s.)

We stayed in holiday homes, little cottages, and five-star hotels. We met many people- friendly and helpful—and our respect for Polynesian culture deepened. Everywhere we went, we encountered people proud of their heritage and deeply connected to the land and sea.

After all, the Polynesians found and settled Hawai‘i by navigating only with the stars; they survived Cook, imperialism, and WWII, made Paul Gauguin famous, and inspired not one, but two Disney movies—without ever losing their sense of identity.

Fiji’s history is as layered as its landscapes. First settled by ocean voyagers over 3,000 years ago, the islands developed complex chieftain systems, intricate trade networks, and a profound relationship with nature. European contact began in the 17th century—and the story took a turn.

In one of the more unusual colonization tales, Fiji didn’t fall to the British through conquest—it was, more or less, gift-wrapped and handed over. The year was 1874. Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau, a powerful Fijian chief who had declared himself “Tui Viti” (King of Fiji), was struggling to actually rule it. Rival chiefs weren’t buying the whole “king” concept, European settlers were stirring up trouble, and to top it off, Cakobau owed a hefty debt to the United States after an American consul’s house was burned down.

Enter the missionaries, who convinced Cakobau to make it someone else’s problem. With their encouragement—and perhaps realizing that governing a chaotic archipelago wasn’t quite as glamorous as it sounded—Cakobau did something bold: he wrote to Queen Victoria and offered her the whole place.

The British were initially hesitant—Fiji wasn’t exactly a prize like India—but eventually, they accepted. On October 10, 1874, in a ceremony held in Levuka, Fiji officially became a British colony—signed over not by force, but by request.

One of the first problems the British encountered was labor. Indigenous Fijians were brave and hardworking, but didn’t see the point in doing unnecessary or uninteresting work. So, the British brought in tens of thousands of Indians to work the sugarcane fields.

All was well for a few decades—until it wasn’t.

After arriving as indentured laborers, the descendants of these Indian workers—now known as Indo-Fijians—found themselves in a strange position: born and raised in Fiji, yet legally barred from owning land. With most land held in communal ownership by Indigenous clans (a system that remains today), Indo-Fijians could only lease land—often on short, insecure terms. This created decades of economic tension and political imbalance, particularly in rural areas where Indo-Fijians worked the land but couldn’t claim it as their own. Although the lease system has since been reformed in many places, the deeper question of belonging—of who owns and who is merely a guest—still lingers in Fijian politics.

Fiji gained independence in 1970 and today it’s a rich blend of Indigenous, Indo-Fijian, and colonial influences—visible in its food, architecture, politics, and religion.

The capital city, Suva, is often overlooked in favor of Fiji’s postcard-perfect islands.

It’s a working city—not a resort—where ministries operate out of colonial buildings and open-air markets spill onto the streets in loud, dusty bursts of life.

Suva’s architecture still bears traces of its British past. The old Government House and the Grand Pacific Hotel—with their wide verandas and fading grandeur—feel like relics from another era. But Suva isn’t frozen in time. Young professionals spill out of office buildings for lunch at roadside cafes, kids fill the parks, and Indo-Fijian tailors stitch colorful fabric into beautiful saris.

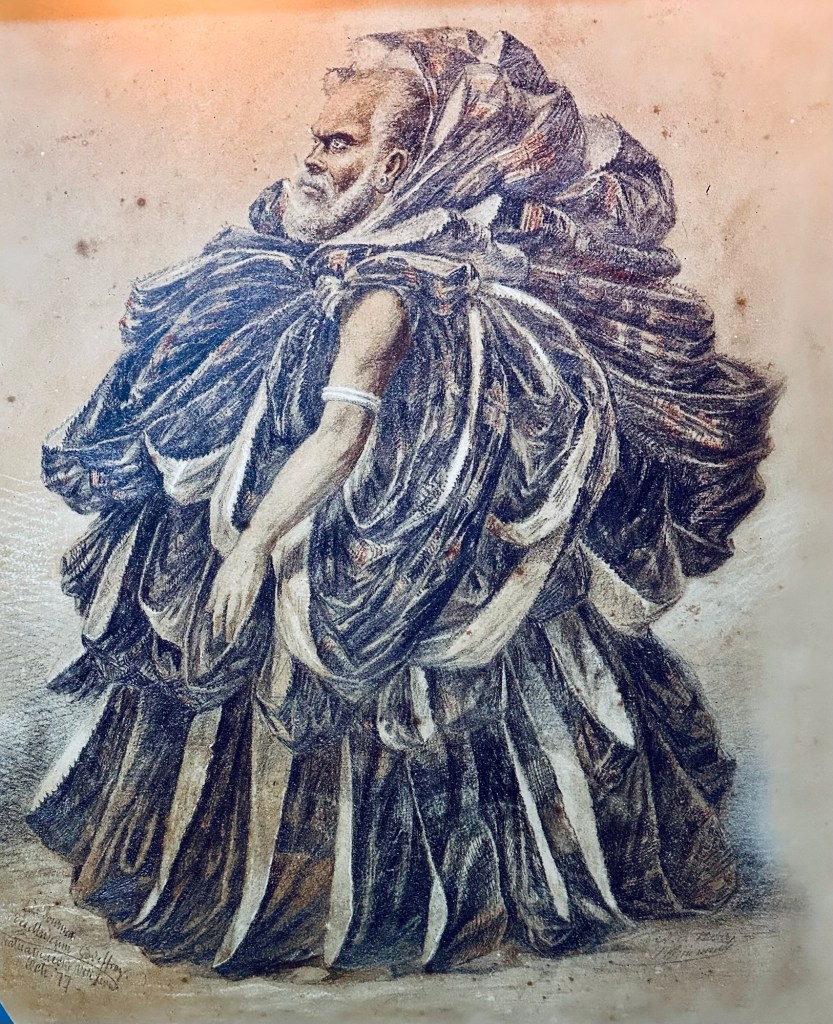

Hidden inside the peaceful Thurston Gardens, the Fiji Museum offers a striking window into the archipelago’s past—from vakas (double-hulled canoes used by Polynesians to settle Hawai‘i) to cannibalism, colonialism, and war.

One of its most famous relics is a timber fragment from the HMS Bounty, the British ship made famous by the 1789 mutiny. Although the mutiny occurred in Tahiti, Captain Bligh famously passed through Fijian waters during his 3,600-mile escape in an open boat—navigating reefs without charts, food, or weapons. Today, a piece of that boat sits in Suva, as a witness to the saga.

But perhaps the most unforgettable display is the one dedicated to Fiji’s cannibal past—featuring cannibal forks, brain scoops, clubs, and ceremonial weapons.

These belonged to the Old Religion: a pre-Christian belief system centered on ancestor spirits (kalou-vu). Different gods were worshiped for war, agriculture, fishing, and trade. Each had its own spirit house and priest (bete), and many required sacrifices—including, at times, human ones.

The Thurston Gardens are lush and serene, and just outside the museum is a small café – The Ginger Garden- that serves fantastic smoothies and salad bowls.

While exploring Suva, we stumbled across a live performance about Blackbirding, a term I hadn’t heard before. In the 1800s, thousands of Melanisians—mainly from the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu—were tricked, kidnapped, or coerced into laboring on plantations in Fiji and Queensland. Conditions were so horrific, it was slavery in all but name.

The performance was raw, emotional, and unforgettable.

Suva doesn’t romanticize itself—and that’s exactly why it’s worth visiting.

Nadi, near the international airport, is practical and useful, with everything from souvenir shops to cash machines.

Some essentials:

• 1 USD ≈ 2.25 FJD. Credit cards are widely accepted.

• Electric outlets: Type I (carry an adapter unless you’re from Australia or New Zealand)

• SIM cards: Vodafone and Digicel for physical SIMs. We used Airalo and Gigsky—both data-only and complementary in coverage.

There’re two ‘must-do’s in Nadi :

Bulaccino, a farm-to-table café, that serves excellent breakfasts and light lunches. We loved it so much, we went twice.

The Sri Siva Subramaniya Swami Temple, elaborately carved and brightly painted, is impressive. To visit it, modest clothing is required. Inside, incense mingles with tropical heat, and the gods stare back at you with serene intensity.

We were lucky to witness a wedding ceremony in the central hall. A host told us that everyone present—bride, groom, families, and guests—had come from New Zealand.

“Why Fiji?” I asked, hoping to hear a romantic story.

He shrugged, nodding toward the couple deep in ritual.

“They wanted to make it an event. So here we all are.”

We visited First Landing Beach, the legendary site where the first Fijians arrived over 3,000 years ago. It’s beautiful—but nearly swallowed by resorts, with just a narrow alley giving locals access to the shore. That soured the experience a bit for us. Instead, we went to Vuda Marina and enjoyed a leisurely lunch at The Boat Shed, watching the boats return from day cruises.

Denarau is a well-designed enclave of gated resorts, golf courses, and marinas. Polished, predictable, and relaxing—ideal if you’ve just landed or are about to leave.

We stayed at a comfortable holiday house on Fantasy Island on arrival and again at a five-star hotel at Denerau before departure. Both were great bases for exploring the northern parts of the island and chilling out.

About 50 kilometers from Denarau, in the fertile Sabeto Valley, the Garden of the Sleeping Giant offers one of Fiji’s most colourful inland excursions.

Originally developed in the 1970s by a Canadian-American actor, the garden was intended to showcase his private orchid collection. Today, it has expanded into a carefully maintained botanical sanctuary featuring over 2,000 varieties of orchids, as well as tropical flowering and native forest plants.

We followed a shaded walking trail and boardwalk that winds through landscaped lawns, lily ponds, and forest groves, all set against the dramatic backdrop of the “Sleeping Giant” mountain ridge, named for its reclining human-like profile. The nature wasn’t coming at us subtly, but in full force—a cacophony of colours, aromas and shapes.

The walk is as tough as you want it to be, and as long as you like. The more we climbed, the more the land opened before us—and the steeper it got.

At the end of the walk, we were offered tall glasses of cold fruit juice and relaxed in the garden’s rustic pavilion—a very welcome Fijian custom.

Driving south from Nadi, the road winds along the Coral Coast, offering stunning views of turquoise lagoons, palm-draped beaches, and tiny villages. Here, you feel Fiji slowing down. Roadside fruit stands sell papayas, pineapples, and coconuts. Children wave as you pass.

This stretch of coastline is more than just a scenic drive—it’s home to some of Fiji’s most accessible coral reefs and cultural sites.

We stopped at the Sigatoka Sand Dunes, a national park protecting the largest archaeological site in the country. Walking across the dunes—some over 60 meters tall—is like entering a desert that forgot it was next to the ocean.

Beneath the sand lie ancient burial sites and pottery shards dating back over 2,500 years. It’s one of the earliest signs of settlement in the Pacific.

The dunes shift constantly, revealing and concealing stories with every wind. And climbing and sliding back the sand dunes ? Real world Disneyland.

Just a short 30-minute drive from Sigatoka, through rolling green hills and sleepy villages, there is the Natadola Beach —wide, white, and elemental. It’s one of the few beaches in Fiji where you can swim all day, no matter the tide. There are a few hotels and resorts around; but mostly it’s just a beautiful communal beach .

We searched for sea shells and sand dollars at the soft afternoon light and watch the young kids play in the surf.

The Coral Coast, running along southern Viti Levu, is one of Fiji’s most visually dramatic stretches. The fringing reef keeps the surf at bay, forming shallow lagoons perfect for reef walks and snorkeling.

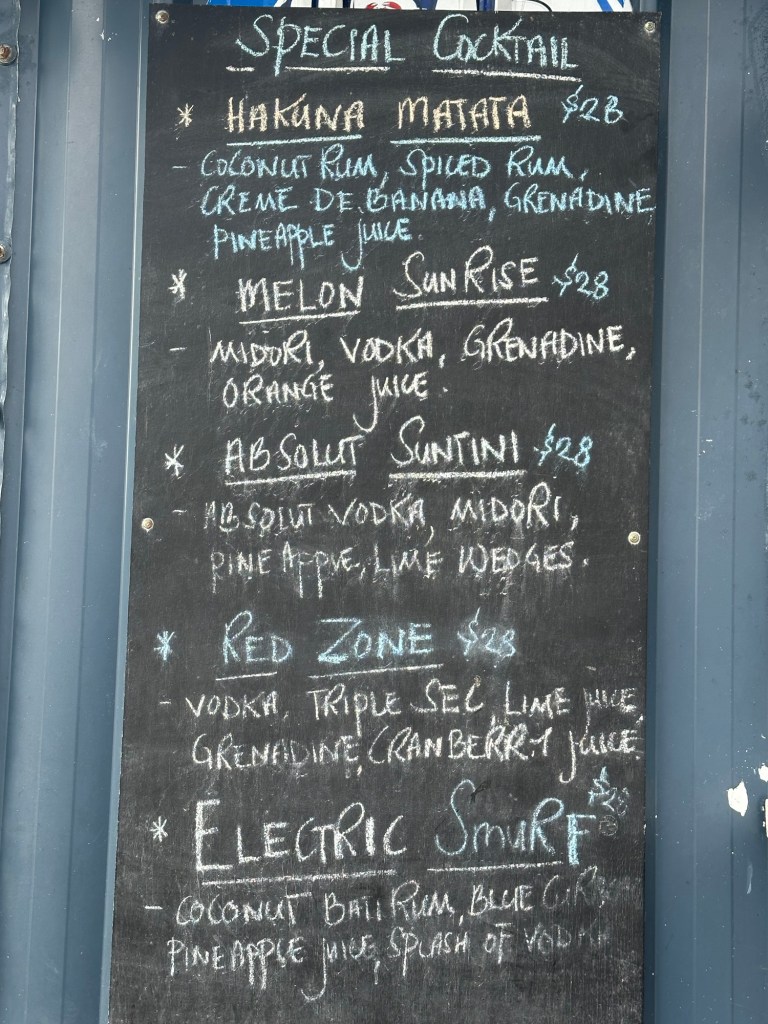

En route, we stopped at a seaside restaurant called the Crab Shack and had one of our most memorable lunches in Fiji.

Sitting on wooden benches, we tasted New Zealand green-lipped mussels, local shrimp, and mud crab—washed down with a lovely rosé—all incredibly delicious.

Another lovely spot was Café Planet, a little place serving excellent coffee and healthy snacks.

We stayed at a tiny cottage surrounded by a lush garden with posh outdoor furniture and private beach access—in the middle of nowhere.

The owner had thoughtfully left some bread, milk, and eggs for us, which came in very handy for breakfast the next day.

She stopped by to check if we needed anything—a polite young woman who also ran an organic egg farm (hence the delicious eggs). She was happy I liked them and told me to just give her a call if I needed more.

I asked her about the place, and she explained that they bought the land just before the pandemic. When restrictions hit, they built the cottage and moved there with their two little kids.

We were their last guests, as they were planning to build a proper house.

Lucky us. And lucky them.

We spent two peaceful days there, syncing with the ebb and flow of the tide, taking long walks on the coast, finding little treasures on the reef left by the last tide—feeling alone in the world apart from a few dogs, feeling renewed and completely in balance.

The nights were spent watching the Southern Sky, trying to spot familiar constellations. (Hint: everything is upside down.)

And, best of all, we had our last Pacific full moon there; just us, the moon and the sound of the waves; feeling blessed and thankful.

One day, we drove to Pacific Harbour, a posh resort community with streets shaded by trees and a few good restaurants.

I loved our stay at that tiny cottage by the sea. The whole experience was rejuvenating.

One day, we took a boat trip to the Mamanuca Islands and spent a full day snorkeling.

Here, the islands are famous. The one where we stopped for lunch was the filming location for Cast Away. Who can forget Tom Hanks, his long hair, and his best buddy, Wilson? The next island was used for Survivor.

These islands, so close to Viti Levu, are home to some of the healthiest coral reefs in the South Pacific, where marine scientists work alongside dive operators to preserve them. They call them the Living Reef.

Dive below the surface and you’ll find hard and soft corals, giant clams, reef sharks, and my favorite—blue staghorn coral.

The silence underwater is total, broken only by the sound of waves and your own breath.

Snorkeling here isn’t just about seeing pretty colors—it’s about understanding fragility. The reefs are alive, complex, and endangered. Rising sea temperatures and bleaching threaten this ecosystem, but local marine reserves and no-fishing zones are part of a larger regional push for sustainability.

Northwest of the Mamanuca group lie the beautiful Yasawa Islands: a remote, rugged chain known for dramatic volcanic peaks, isolated beaches, and some of the clearest waters in the South Pacific. Since we chose to spend more time on the main islands, we didn’t make it there. Well, there’s always a next time.

On Vanua Levu, Savusavu rests inside a protected bay that has long been a favorite anchorage for sailors.

Unlike Viti Levu’s resort-lined coasts, Savusavu feels more real. There’s only one main street, edged by small grocers, coconut oil cooperatives and street vendors.

The town’s calm harbor—often mirror-still—hosts a small expat community living on boats or in hillside homes. They’re drawn to the island for its quiet beauty, authenticity, and sense of seclusion.

In Fiji, most men dress in smart shirts and long skirts called sulu. And of course, the boys in our group had to try them. I have to say, I find the combo comfortable and quite chic.

After some shopping, we had a lovely lunch at the restaurant of the harbor club on fresh lobsters and rose wine.

A la vie en rose moment to remember.

Off the southern coast of Viti Levu, Beqa is home to a cultural practice : firewalking, or vilavilairevo. Although nowadays it is perfomed mainly for tourist groups, it’s a sacred ritual rooted in myth, connecting them to their ancestors.

Firewalking requires intense spiritual discipline, ritual fasting, and purification. Only those who have gone through proper rites are allowed to walk.

The ceremony unfolds slowly. Young men gather around smoldering stones that have been heating for hours. The act isn’t about proving bravery but about spiritual preparation, often linked to tabu (sacred) obligations and initiation.

Firewalking offers a rare glimpse into Fiji’s living traditions—a culture where myth and belief still walk hand-in-hand (or barefoot) over glowing embers.

Afterward, a lovely young woman invited us to the village for the kava ceremony; answering our questions about her village, and the rituals that we are witnessing.

In Beqa, they have a strict dress code mostly applied to women. No shorts or pants – the legs must not show. If you haven’t bring your own pareo, they offer them for a token fee.

After a short walk, we arrived at her village and toured around. It was clean and well organised. I was surprised to find 2 or 3 different churches for such a small community, but who am I to judge these people living on the edge of western civilisation, on an island that is open to every whim of the mighty Pacific ocean.

Then, the kava ceremony begins. Kava—made from the ground root of the yaqona plant—doesn’t intoxicate but gently numbs the tongue and quiets the mind. Served in a coconut shell and passed respectfully from hand to hand, it’s a medium for hospitality, storytelling, and social cohesion.

Afterwards, on the road back, I asked our guide if she drinks kava. She does. When she’s a bit down, as a pick me up; or when she has a very busy day ahead; because it kills hunger and gives energy.

‘Hmmm- I thought. This is interesting. ‘

Then she warned me . ‘Too much kava, you go kava walking. ‘

‘What is that ?’ I asked.

‘When young fellas drink too much kava, they think they can walk on water. They go kava walking, past the houses, past the beach, into the ocean. ‘

‘And ?’

‘And, they keep walking. ‘

Does it taste good ? No.

Is it safe, or even sanitary ? Not really.

Will I do it again ? Absolutely.

Traveling through the Polynesian islands—especially Tahiti and Fiji—stirred something deeper in me: a reflection on the meaning of travel, and our bond with the natural world.

These islands are not mere destinations on a map, but living, breathing communities—rooted in ancient traditions, surrounded by seas as fragile as they are magnificent.

With an economy totally dependent on tourism, the pandemic, a painful but distant memory for most of us, was still very real to them. Everywhere we went, somebody always mentioned the devastating effects of it; both economic and social.

Mass tourism, while boosting local economies, can often strain fragile ecosystems and alter the very cultures that visitors come to experience.

These islands need us—but not just as tourists to bring in the much needed cash, but as mindful travelers; to enjoy, to share and not to disrupt.

I believe, the oceans that cradle these islands, and the people who live in harmony with them, hold a key to our own future.

To protect them is, in many ways, to protect ourselves.

If you want to read about the history and culture of the Pacific Islands, check out below books from James Michener. Both are classics :

Tales of South Pacific and Return to Paradise

Lonely Planet’s Fiji guide also helped me plan parts of this voyage.

Please note that some of the links help support the blog, at no extra cost to you. Thanks, truly.